What Could Go Right?

The Upside of Optimistic Future Outlooks in an Increasingly Nihilist Present

“The most likely result of building a superhumanly smart AI, under anything remotely like the current circumstances, is that literally everyone on Earth will die.” - Eliezer Yudkowsky, Time Magazine, March 29, 2023

No, the above quote isn’t pulled from an Orwell science fiction novel or stated by the supercomputer AM in Harlan Ellison’s “I Have No Mouth, and I Must Scream.” It’s a genuine warning and insight from one of the earliest and most significant Artificial intelligence researchers. More importantly, however, is that it captures a broader trend amongst the general populace. It has become commonplace for people to believe that the future is not uncertain, but rather that the future is inevitable and doomed. As if humanity is slowly drifting towards the edge of a waterfall, drop by drop, on a small canoe, helpless to save ourselves. Despite this common belief, I posit the opposite stance: the future is brighter than ever, and being optimistic presents the highest upside, both financially and eudaimonically. Optimism isn’t naivety. It's a strategic, historically sound, and necessary response to techno-nihilism

This is not the first time that the human race has faced a transformative technology with great fear about the second-order consequences of its potential. From the printing press to the steam engine and from the telephone to the internet, every technological breakthrough has been met with mass panic, narratives of societal collapse, and fears of mainstream addiction. Despite all this, the fact that you are reading this now proves that such pessimism is almost always wrong, and those who bet smartly on optimistic progress become the ones who shape it. To understand this natural fear response not as a prophecy, but as a pattern of human nature, one only needs to look to the past.

We’ve Been Here Before: The Historical Precedent of Human Nature

Artificial Intelligence and AGI are unprecedented, yes, but the mass human panic is not. To understand techno-nihilism as a cultural reflex rather than a sign of greater awareness, one must keep in mind one concept I propose:

“History doesn’t repeat; Human Nature does.”

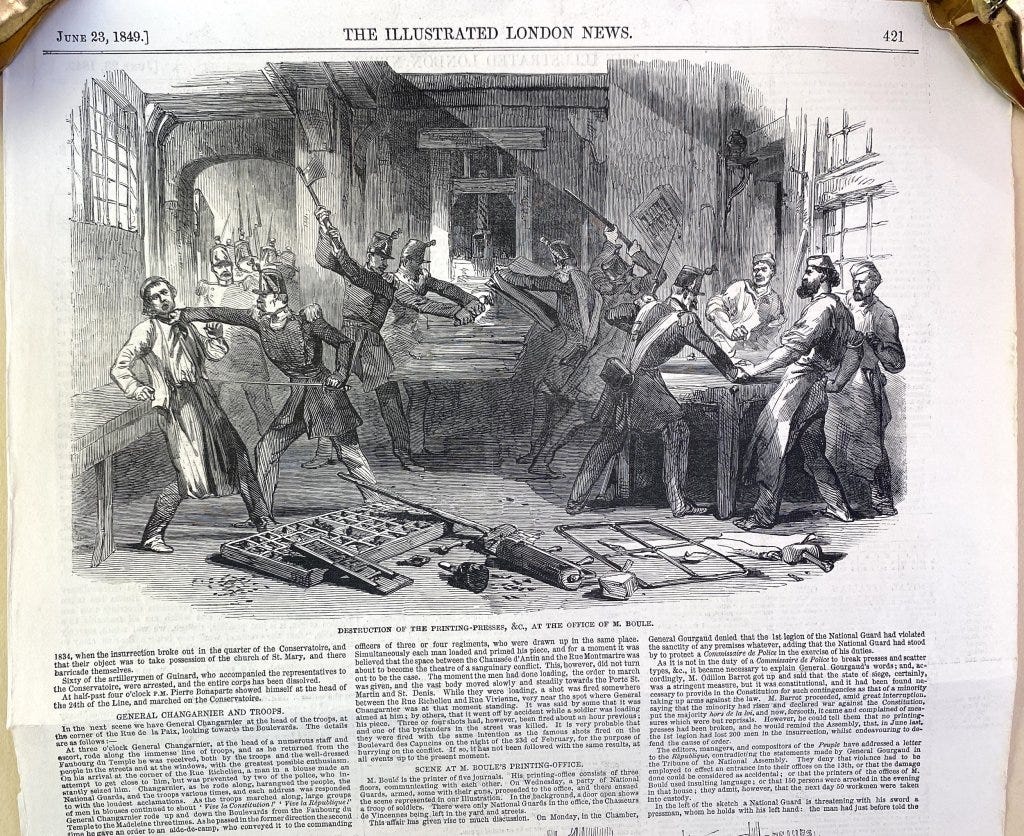

To prove this, let's rewind quickly to the 15th century. A revolutionary invention, Gutenberg’s printing press, catalyzed a seismic shift in the propagation of knowledge. In hindsight, it's easy to think that everyone at the time would’ve been ecstatic about books and writing being more accessible. Sadly, such was not the case, as Scholars of the time feared that printing would weaken human memory, corrupt knowledge, and flood society with misinformation (sound familiar?). Guilds of scribes destroyed printing presses and chased book merchants out of town like witches. Religious leaders condemned the new Bibles made from the printing press as the Devil’s work, most likely because it threatened their monopolistic business. Monk-scribes, like Johannes Trithemius, cried that: “Printed books will never be the equivalent of handwritten codices, especially since printed books are often deficient in spelling and appearance.

Techno-nihilism has even more ancient roots, with Socrates himself warning people in Phaedrus that writing was dangerous, claiming that:

“For this discovery (Writing) of yours will create forgetfulness in the learners' souls, because they will not use their memories; they will trust to the external written characters and not remember of themselves. The specific which you have discovered is an aid not to memory, but to reminiscence, and you give your disciples not truth, but only the semblance of truth…”

At first, this excerpt seems quite ridiculous, but when you replace “Writing” with any other technology, you begin to hear exactly what people say today. People complaining that we need to “return” to how things were before, with the irony being that previous generations said the same stuff in those “before” times.

Or what about when electricity was first introduced in the 19th century? Critics warned that electricity would lead to unnatural lifestyles, moral degradation, and brain damage. Articles in the 1800s Scientific American Magazine argued that electric light would disrupt the circadian rhythm and believed that excessive electrical use would lead to nervous disorders. While electricity has certainly changed work schedules and city structures, it has also revolutionized medicine, communication, industry, and extended human lifespans.

Even just recently, with the rise of the internet, critics warned us that ubiquitous access to information would make us all lazy, dumb, and shallow. Foretelling a desolate future of brain-dead, broken people. In his 1992 book, Technopoly, Neil Postman echoed fears that information would lose all its meaning, saying, “Information has become a form of garbage.” While many critics of the internet weren’t entirely wrong, we have become less physically connected, and distractions are abundant; however, the internet has empowered activists, educated billions, provided more people with jobs, and preserved human connection during dark times (the pandemic). The internet didn’t destroy civilization; it just changed it. If there is one thing the human race is above all, it's that we are incredibly adaptable.

Now, to steelman the opposing view: of course, not every technological breakthrough has been a clear-cut positive. The introduction of gunpowder to Europe at the end of the Middle Ages marked the beginning of a period of prolonged war, which reached its peak with the World Wars in the 20th century. Furthermore, leading AI risk thought leaders

about the gradual disempowerment, characterized by systems that erode human agency without any “doomsday” moment. To their credit, anticipating failure modes or backdoors is a responsible approach, but resigning oneself to them as inevitabilities is not. Resignation to “doom” excludes a critical nuance: none of those technologies actually “doomed” us, but instead transformed us. Dark technological periods did not diminish our agency; they redefined the stakes and demanded a more robust moral framework for humanity to live by. My goal is not to say that technologies can’t go wrong; instead, I reject the idea that these wrong turns are inevitable and fixed. Progress has never been linear, but pessimism offers no help in shaping our trajectory; only optimism does.

In every one of the techno-nihilist moments, the pattern was the same: a groundbreaking technology was created, people responded with fears of the end of civilization, humanity survived, transformed, and thrived. While AI may present new challenges around control and alignment that differ from past technological advancements, the pattern of the superiority of engaged optimism over passive pessimism remains relevant. Fear is a very natural human response; however, betting on fear in the long run has historically been the incorrect move. Which begs the question, what do we bet on? Well, betting on reinvention, innovation, and progress is why we have civil rights, modern medicine, electricity, and so much more.

So, the choice is yours: will you follow the panic playbook of the past, or recognize the pattern and choose to build optimistically?

Thriving > Surviving: Optimism as a Strategy

In today’s world, people seem to view optimism as akin to naivety, but this couldn’t be further from the truth. People often conflate optimism with dreamers who are soft, idealistic, or even delusional, as if optimists are blind to the exponential technological shift that is happening. This notion is a blatant misunderstanding of optimism. Optimism is not a blind faith in a sunshine and rainbows outcome. Optimism is the realization and conviction that building something that makes the world better is more worthwhile than wallowing in despair and helplessness.

To prove this rationale, let’s take a look at a famous thought problem: Pascal’s wager. In Pascal’s original wager, he proposed that believing in God was the safer, more rational choice. He argued that if you were right, you would gain infinite reward (eternal life/heaven); whereas if you were wrong, you would lose little (normal death). While his original wager does leave out many nuances about faith and other concepts, I believe his wager better applies to optimism vs. pessimism in future outlooks:

If you bet on an optimistic future and you’re right, you reap immense benefits materially (investments, unicorn businesses), socially (relationships and reputation), and existentially (eudaimonia, purpose, self-actualization).

If you bet on optimism and turn out to be wrong: You lived a meaningful life, remaining happy and hopeful before the collapse, which would've happened either way.

If you bet on a dystopian future and you’re right: Yes, maybe you are right. Perhaps you are one of the winners: a tech founder who survived the collapse and now lives in a remote, off-grid location with some form of AI-augmented immortality, while society crumbles around you. However, is that outcome not spiritually void? Thriving while the rest of humanity decays is just a sugar-coated exile, regardless of the few “elite” making it or not.

If you bet on dystopia and you’re wrong: Congratulations, you lived in immense fear and missed every opportunity, ultimately contributing nothing to society other than being a nervous wreck.

The issue is not that the doomer case is implausible or unsophisticated. The problem is that it offers no actual moral or communal upside. Such a view is simply resignation, a form of hedge or insulation against a future that is seen as fixed. Additionally, there appears to be a peculiar culture surrounding doomerism in today’s society, as if we’ve come to celebrate it as a welcome outlook. We like to race and compete with each other to post the most extreme, Orwellian version of humanity’s collapse and decline. Spewing such things as: AI will make us slaves, deepfakes will destroy all human-made content, dopamine loops will lead us to rot in VR for eternity, and so much more. Preparation for worst-case scenarios is always thoughtful, but becoming slaves to the belief in such a future and succumbing to helplessness is what is foolish.

Furthermore, doomerism fosters a passive relationship with the future, suggesting that the future is fixed and predestined, as if we have no power to influence or change it. This is precisely why doomerism has become so popular: it gives people an excuse for inaction, laziness, and cynicism. Since nothing can be done, nothing should be done, right? Doomerism rewards disengagement, and today’s generation lacks the agency to improve themselves; is AI really to blame?

Optimism, as a foil, forces participation. Optimism asks more of you. Optimism forces you to believe in yourself. Optimism is working hard today for the benefit of your future self. Optimism insists that you can make the future better and that your choices today matter.

The irony of AI-doomer worldviews is that “success” or “winning” is seen simply as survival. Escape to an island, build a massive bunker, upload your brain, and become wealthy enough to cryogenically freeze your body, etc. These are extremely poor definitions of success. Real success, real winning, is thriving, not simply surviving. More specifically: thriving with others.

Furthermore, reducing humans to pure dopamine slaves, as many AI-doomers do, overlooks every single human advancement, from Mozart to CRISPR to the Moon Landing. Our ambitions do not vanish the instant we get access to pleasure; if that were true, humanity would have been “one-shotted” long ago by drugs and other hedonistic loops. However, history would once again show us that meaning emerges and is catalyzed when resources become more abundant. More freedom has always spurred humanity to seek something higher and “reach for the stars,” both physically and metaphorically. Pessimism is a self-fulfilling prophecy; it saps all the will from us. Optimism, however, is a network effect. Optimism is contagious; it spreads through and lights up rooms. The more people who believe that the future can and will be better, the more we invest in making it a reality.

Optimism is not blind faith; it's a rational engagement with the future. It's a driving, all-consuming belief that our fate is not fixed, that problems can be solved, that value can be created, and that we can thrive even in the face of a tsunami of change. Now, I urge you to weigh the potential outcomes and perform your future version of Pascal’s wager. I, for one, find that optimism is the clear choice both emotionally and strategically.

Building the future: What Could Go Right

While being optimistic is an excellent frame of mind for the future, without action or application, it's pretty useless. To truly shape the future, one must make the correct optimistic bet. Now, more than ever, it is essential to reflect deeply on a single question. What could (and has the best chance to) go right?

One of the most critical and optimistic bets to make is to view AI as a collaborator and a form of leverage, rather than a competitor to humanity. Yes, AI has and will replace many monotonous tasks, taking on a variety of such jobs. However, the freedom it will create will enable humans to spend more time on more creative endeavors. After all, creativity has always been humanity’s greatest gift. Artificial intelligence is not robbing us of meaning; it's giving us the time and space to pursue the meaning we desire. With that being said, more freedom in our lives also means more risk of succumbing to distractions or hedonistic pleasures. The most significant edge in the coming age will be discipline, agency, and drive. Being intelligent is excellent, but being intentional is what is necessary. The challenge presented by AI is whether we will use it to become who we want to be or let it merely highlight what we are passively.

The questions posed by AI aren't merely technical; they're deeply personal:

Will we choose to build systems that reflect our highest virtues or settle for ones that enable our hedonistic desires?

Will we leverage AI to better ourselves or use it to escape reality?

Will we participate in shaping a better future, or outsource it to entropy

The absolute core of the optimistic stance is not a blind belief in better outcomes, but a firm belief in our ability to choose better directions and shape our future. Progress is by no means a guarantee; it's a wager that must be placed with courage.

The question is not whether AI poses risks; it does. The question is whether we will approach those risks with the agency, creativity, and active relationship with the future that has always driven human progress.